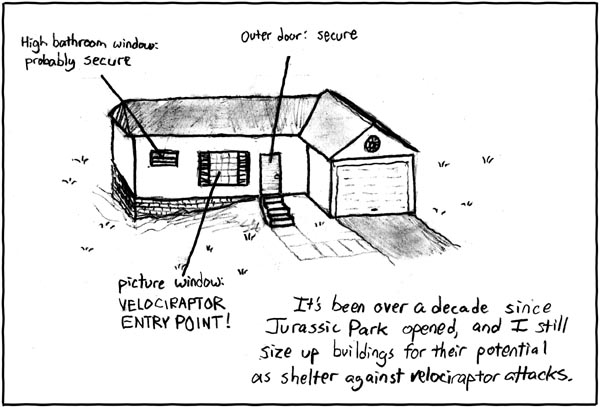

Another week, another RITA Award-winner to analyze.

Today's book is Mary Jo Putney's The Rake and the Reformer, the winner of Best Regency Romance in 1990. I hadn't read this one before, which means it's harder to pick out the details of technique. One thing, however, leapt right out at me: these characters felt like adults.

It's hard, in the world of the Regency romance, to get characters that feel like grown-ups. Luckily, the trend of the youthful, untouched 18-year-old who enlivens the older, jaded man is fading into the background -- hearts, Madame Heyer godsavethequeen -- but it still lurks in a lot of the structure.

I'm not the only one who noticed this aspect of the book. The notorious Mrs. Giggles said as much in her review: "oh, those days when heroines don't behave like ten-year olds!" But it's a thing that is very hard to pinpoint and emulate, much as I would like to. How do you quantify such a thing? The impression must be made in a series of tiny moments, well-placed words, and vividly well-drawn scenes. It requires a prodigious imagination, an astonishing amount of work, or -- this is the most likely -- both. It is a great achievement.

Mrs. Giggles' review brought something else to light: there are two editions of this book. I've read the earliest -- the Signet edition depicted to the right there -- but La Giggles has obviously read the re-release, and has this criticism to offer: "Reggie doesn't act like a jerk. But isn't he supposed to be a jerk?. . . Reggie is portrayed too nicely and too sympathetically."

Um -- really?

Because about halfway through the book, Reggie -- our hero, who is a full-on alcoholic with blackouts and health troubles -- lapses from his planned sobriety, gets roaring drunk, and tries to rape our heroine, whom he's already on mutually-consented-to-kissing terms with. Some choice phrases he uses during this scene: "Coyness don't suit you, Allie. I know what you want, and be m-more than happy to give it to you . . . Don't you think I know why you're always twitching around me? Underneath that proper face you're as hot as they come, and we both know it." And Allie is horrified and ashamed and fearful but not so fearful that it prevents her from hitting him with any number of heavy objects and yelling and fighting him off. And remember, this is halfway through our romance.

Reading this scene, I felt it was pushing the envelope -- or else it was harkening back to the not-so-long-ago days of Sweet, Savage Love and that one romance novel I read where the heroine was raped by Wagner. (Yes, THE Wagner. It was strange.) And because it was scary, and dangerous, and unprovoked, and mean, it raised the stakes like they rarely get raised for rakes these days. Every frequent romance reader knows that the dangerous rake with the dastardly reputation is not really that bad, deep down. A heroine's reputation may be ruined in the course of the book by her association with the hero, but usually instances of actual, honest-to-goodness abuse are limited to emotional distance and a slight coolness soon shattered by the Sexy Sexy Times the hero and heroine insist on having at intervals convenient to the narrative.

Reggie, on the other hand, is actually, physically, emotionally dangerous. He may well be a terrible choice as a lover, and not simply because Allie's reputation may suffer. She has a strong incentive to not want to spend time with Reggie ever again, after this incident. Of course, they end up happily -- but Ms. Putney makes it a plausible ending, which Reggie has to earn and work toward. Which means, naturally, that this scene's location in the exact center of the novel is no coincidence, but rather a canny bit of planning on the author's part.

Yes, there are plenty of moments where Reggie is otherwise proved not as bad as reputation would have it, but it does matter that we have this particular scene played out with no other witnesses, just Allie and Reggie -- and the reader.

At least, the reader who gets the Signet edition. When romances are reissued, it is not uncommon for the author to also take the opportunity to rewrite them, just a little bit. A book is never really finished, not even for novice aspirants like myself. And these are people Ms. Putney spent a lot of time with when she created them, which the reissue allowed her to revisit and relearn. Mrs. Giggles' opinion that Reggie was too sympathetic either indicates that her standards of villainy are far more demanding than mine -- or else quite a bit of the book was revised when it was put out under the shortened title, The Rake.

What I want to know is this: did she change anything about the near-rape in the reissue? The cheap copy I found on the interwebs should tell me: further bulletins as events warrant.

You show him, bubblegum-tongue lady.

You show him, bubblegum-tongue lady.

It's been months since I graduated, and there have been many days with splendid weather, but even with a wide-open schedule it feels like time runs like sand through clenching fingers. All I'm left with is grit. Why is it so easy to do things when others compel us, and so hard to do things we dream for ourselves? Especially when they are a little out of the way, or rearrange the normal shape of a schedule?

It's been months since I graduated, and there have been many days with splendid weather, but even with a wide-open schedule it feels like time runs like sand through clenching fingers. All I'm left with is grit. Why is it so easy to do things when others compel us, and so hard to do things we dream for ourselves? Especially when they are a little out of the way, or rearrange the normal shape of a schedule? Finally, something in me rolled over and pointed to Thursday, February 4. This would be Juanita Bay Park Day (my inner monologue tends to rhyme and alliterate to an alarming extent). But the designated day dawned gray and lackluster, with the bored fuzzy sky that will defeat my poor little Canon digital every time. And then! At 3:00! I looked outside to see a break in the clouds had opened and pouring down from the heavens was the kind of golden, late-afternoon sunshine that's so thick you can almost taste it like honey upon the tongue.

Finally, something in me rolled over and pointed to Thursday, February 4. This would be Juanita Bay Park Day (my inner monologue tends to rhyme and alliterate to an alarming extent). But the designated day dawned gray and lackluster, with the bored fuzzy sky that will defeat my poor little Canon digital every time. And then! At 3:00! I looked outside to see a break in the clouds had opened and pouring down from the heavens was the kind of golden, late-afternoon sunshine that's so thick you can almost taste it like honey upon the tongue.