Lately I've been thinking a lot about the Bechdel test and what it reveals about the film industry. And there's been at least one post I could find on a Bechdel standard for video games as well, which is interesting, even though I could dispute a whole bunch of points in the post (such as: whether or not fighting is acceptable as interaction between female characters). And it goes without saying that many movies and games do not pass either the original or Bechdel 2.0.

There's a recent Bechdel variation for dance music (a song has to be about something other than "drunk behavior and hookups") and one for the television industry, which says that in order to pass every episode of a show has to have two named female characters who talk about something other than a man.

And then -- of course -- I got to thinking about romance novels. How might the Bechdel test apply?

Oh, sure, romances are jam-packed with female characters, usually -- but usually those conversations revolve entirely around men (or marriage, or babies, which are weak passes for that third rule, in my opinion). And I tend to read historicals and especially regencies, where women's official lives historically really did center around marriage and family and only the lower classes had that tawdry making-a-living thing to consider but we don't really write romance novels about the lower classes unless they end up in the upper classes at the end.

Of course, the whole point of the romance genre is the union of hero and heroine, however that is accomplished. It's important to remember that the hero spends quite a bit of time talking about the heroine with other characters. It's not like the heroine is a secondary consideration the way a female character can be in, say, an action flick. And so maybe the Bechdel test needs to be tweaked for romance novels the way Daniel Feit tweaked it for video games.

All this goes back to the age-old question of whether or not romance novels are feminist texts, or tools of the patriarchy. Whether they subvert or support gender roles and the accompanying expectations. This question is entirely unanswerable, because for every romance novel that does the former you could name one that does the latter. I have come to believe that reading and writing romance novels are very feminist acts. Because there is nothing that the chauvinistic, patriarchal elements of literary culture devalue more than romance novels and the women who read them. You don't need me to tell you this -- every romance reader has had that moment of revelation, where a new acquaintance sees a shelf or coffee table sporting a sunset-hued, mullet-bedecked, cleavage-revealing cover and gets that "I'm mentally taking a step back" gleam in their eye. They see a romance novel and question your taste, your intelligence, and your connection with reality. This is starting to change, thankfully, but even now the experience is far from rare.

Romance novels are written for women, and by women, and many millions of women get together in the world or on the internet and talk to one another about them. In some sense, then, it hardly matters what the texts themselves say, or even whether they're any good (and let's face it, not all of them are).

But sometimes, you read about a hero who's a little too alpha, or a heroine who's a little too self-sacrificing, or you start to worry about the dearth of LGBT characters (who tend especially to be erased/effaced in historicals, though increasingly less so in contemporaries) and you remember the rape-y romance days of yore and realize that we should probably still keep an eye on things from a feminist standpoint.

So what would a Bechdel test for historical romance novels look like? One thing the original Bechdel never really gets to address is what counts as a conversation. Imagine two ladies in a drawing room: "Tea? Yes, please. I like your dress . . . So how do you feel about [insert dudely protagonist here]?" Technically a pass -- but it feels like a cop-out. Yet a startling number of movies fail even something this simple -- which is where the test proves that it is powerful, even when it seems overly simple at first glance. To really separate the wheat from the chaff we need something as revealing about historical romances. Where is the point at which today's historicals have a tendency to let down modern readers?

Where else? Sex.

I'm going to keep the first rule pretty much intact: a historical romance should have at least two female characters.

The second rule of the original Bechdel, that the two characters talk to each other, may need a little more clarifying when we consider novels, which tend to be much wordier than movies. (Get a load of Captain Obvious here.) It's nearly impossible to think of a historical romance where two female characters don't talk to one another, since the divide between gender roles is usually much starker than in either contemporary romances or the modern, real world. We need something more specific.

I would suggest that we begin by considering the absence/insignificance of the Evil Other Woman.

You all know the EOW. She is beautiful, but in a slutty, shameful way, and is frequently described with the word "overblown" or something similar. She's catty and competitive and gossipy and immoral and blatantly attempting to steal the hero from under our heroine's nose. Sometimes she's an ex-lover, sometimes she's a current soon-to-be-jilted mistress, sometimes she's just after a man she wants and doesn't care whom she has to hurt to get him. (One of my favorite tricks of Julia Quinn's is that the Evil Other Woman in three of her novels is the same woman, Cressida Twombley, née Cowper, and she's more of a social than a romantic rival.) And usually, when the EOW is around, there is a scene with her and the heroine where she reveals what a completely rotten person she is underneath that sexy façade. I'm not saying a good old-fashioned argument can't pass this part of the test -- I'm as big a fan of the epic takedown of Lady Catherine de Bourgh as you're likely to find -- but it's critical to note that Lady C. is not a romantic rival, and that most of that conversation is about Elizabeth herself and what she does or does not want. Whereas with the EOW, you get a polarizing, binary system along the familiar lines of virgin/whore, with the hero blithely existing as a prize for women to cut one another's throats for.

In short, I don't think that should count. So, part two: two female characters have a conversation that is not about their mutual sexypants feelings for the hero.

And now, the third part, which is the tricky bit. I think even historical romances should be judged on their level of sex-positivity.

There are two kinds of sex in historicals: hero/heroine sex, and the sex everyone else is having (premarital sex, adulterous affairs, homosexual sex, orgies). For the purposes of this analysis, we are going to ignore rape, pedophilia, and the like -- because it doesn't count as sex anyways, does it. DOES IT.

NO IT DOES NOT.

Ahem.

Hero/heroine sex is always good, redemptive, and/or irresistible. If there are hero/heroine sex scenes that are unsatisfying or creepy, these are 'fixed' in the course of the plot. (For instance, in Mary Jo Putney's The Rake, where the heroine thinks the hero is only attracted to her when he's drunk.) But the sex between secondary characters, or between the hero/heroine and other characters in the past, can be presented as good, or terrible, or dirty, or immoral, or any number of other things. These secondary sexual scenes provide a much clearer window on the sexual morality of an individual book, much more so than the scenes between hero and heroine.

For instance, in a romance I finished recently, a secondary character was being blackmailed by the heroine's father. The victim's secret was that his dead older brother, the heir to a title, had preferred to sleep with men. When the heroine learns this, she is shocked and appalled and disgusted. And I felt a little let down, because the heroine and the hero had spent about half the book struggling with their inability to be in a room together for five minutes without clothes flying off and orgasms happening all over the rug. Who were they to judge someone else's attraction? I know, it's historically accurate for people of the early nineteenth century to consider sodomy appalling. But we do not live in the early nineteenth century, and there's plenty of room in romance for a little anachronism. There always has been.

Another example: Cheryl Holt's A Taste of Temptation, which opens with one of the more tired romance-novel clichés out there: our heroine is applying for the position of governess, and is cornered and groped by the hero's half-brother. Our hero, despite having just lectured his half-brother to stop groping servants and being such an idiotic horndog one page earlier, calls the heroine a flirt and a trollop and has her booted out of the house without letting her explain that being flirtatious and being grabbed are not the same thing. They never get around to clearing this up, because later they get too distracted by accusing one another of liking sex, as though liking sex were something you didn't want in a romantic partner. (Side note: while looking at reviews of Cheryl Holt's other books, I found one that supposedly has a really wonderful historical treatment of a lesbian romance. The book is in the mail, and a report is forthcoming.)

A case on the opposite side: Gail Carriger's paranormal steampunk romance Soulless, which I cannot recommend highly enough. At the end the sexy werewolf hero ends up sans clothes and surrounded by a coterie of frivolous gay vampires, who keep finding excuses to drop things so he'll have to bend over and pick them up. And our hero smiles, and knows what they're up to, and indulges them anyway. Silly vampires, he seems to say -- go ahead and ogle. It does not freak me out, or threaten the very fun sexytime I shall have with my soon-to-be-wife.

The third criteria, then, goes something like this: sex between the hero and heroine should not be presented as morally superior to every other kind of sex. Sex itself is not inherently dirty; it is a human need. Hero/heroine sex can still be special and mind-blowingly awesome -- because we all like reading about awesome sex -- but it is not in a separate, special moral category of its own.

This means: a secondary character trapped in a loveless marriage is not automatically vilified for having an adulterous affair. Homosexual sex is not presented as inherently horrific, or at least it should not horrify our main characters. A hero does not get jealous if the heroine has had satisfying sex before she met him, and the heroine does not consider the hero's greater sexual experience a moral failing that her true love/sexual purity must correct.

So there we are, a rough Bechdel for historical romance:

1. Must have at least two female characters.

2. Who talk about something other than their mutual sexual interest in the hero.

3. Whose sexual relationship with the heroine is not presented as intrinsically more moral than other sexual relationships.

Authors I can think of off the top of my head who pass this test quite frequently: Julia Quinn, Loretta Chase.

Imagine, for a moment, that you are a graduate student teaching assistant in an undergraduate film class at a large state university. You are poorly paid, and entirely untrained. You have a full courseload of your own, and you are teaching a subject in which you have no expertise. Though your union contract stipulates you may only work a certain number of hours per week, this simply means the professors who are in charge of you assume you will work as hard as necessary to finish whatever they assign you within that set length of time. They will expect you to adapt to their plans, and they will not change those plans even if it becomes absurdly obvious that ten allotted hours is not enough time to grade sixty ten-page papers, read all the course's assigned texts, and create a discussion plan for two class sections.

You are also the first line of professorial defense against the unwashed hordes of undergraduates, and so you are the one the students come to with doctor's notes, parents' notes, emails from home when they are sick. At some point, one student will come to you with a note from a doctor or a professor or the school's disability office. That note will say: there is an issue I am going to have, which conflicts with certain expectations for this class. Will you adapt those expectations?

Imagine, for a moment, that you are a graduate student teaching assistant in an undergraduate film class at a large state university. You are poorly paid, and entirely untrained. You have a full courseload of your own, and you are teaching a subject in which you have no expertise. Though your union contract stipulates you may only work a certain number of hours per week, this simply means the professors who are in charge of you assume you will work as hard as necessary to finish whatever they assign you within that set length of time. They will expect you to adapt to their plans, and they will not change those plans even if it becomes absurdly obvious that ten allotted hours is not enough time to grade sixty ten-page papers, read all the course's assigned texts, and create a discussion plan for two class sections.

You are also the first line of professorial defense against the unwashed hordes of undergraduates, and so you are the one the students come to with doctor's notes, parents' notes, emails from home when they are sick. At some point, one student will come to you with a note from a doctor or a professor or the school's disability office. That note will say: there is an issue I am going to have, which conflicts with certain expectations for this class. Will you adapt those expectations?

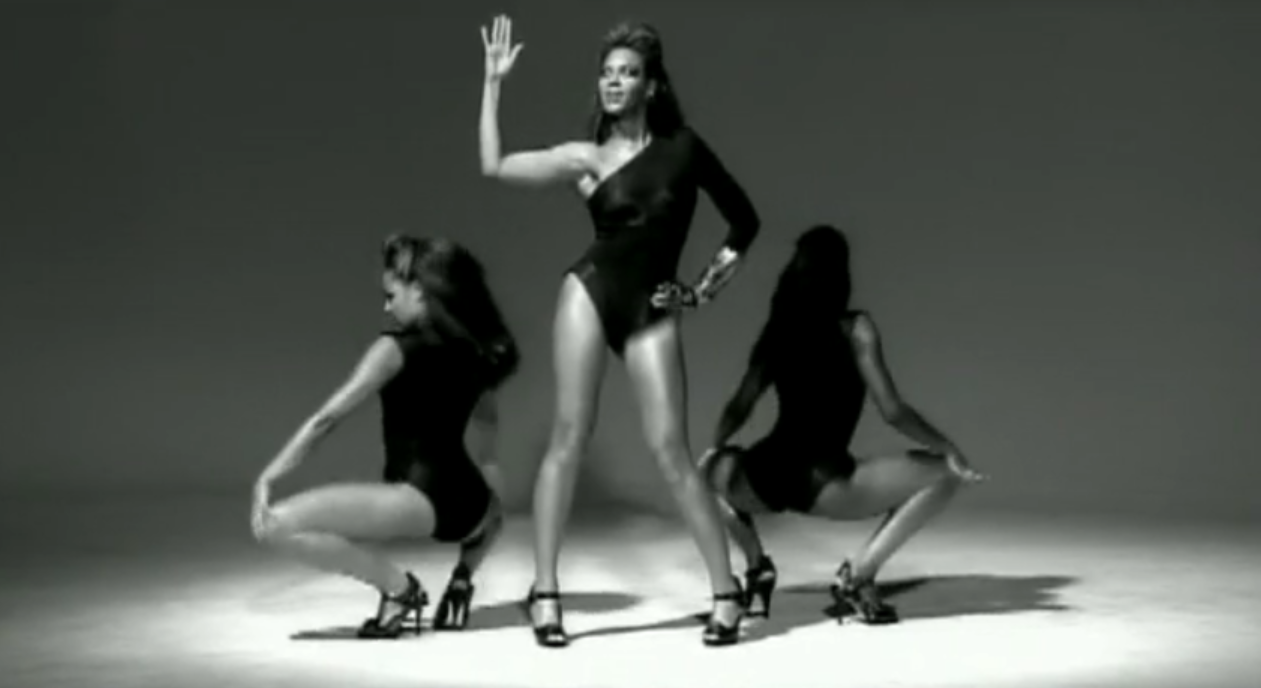

You show him, bubblegum-tongue lady.

You show him, bubblegum-tongue lady.