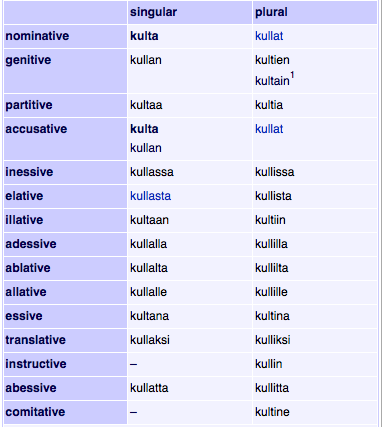

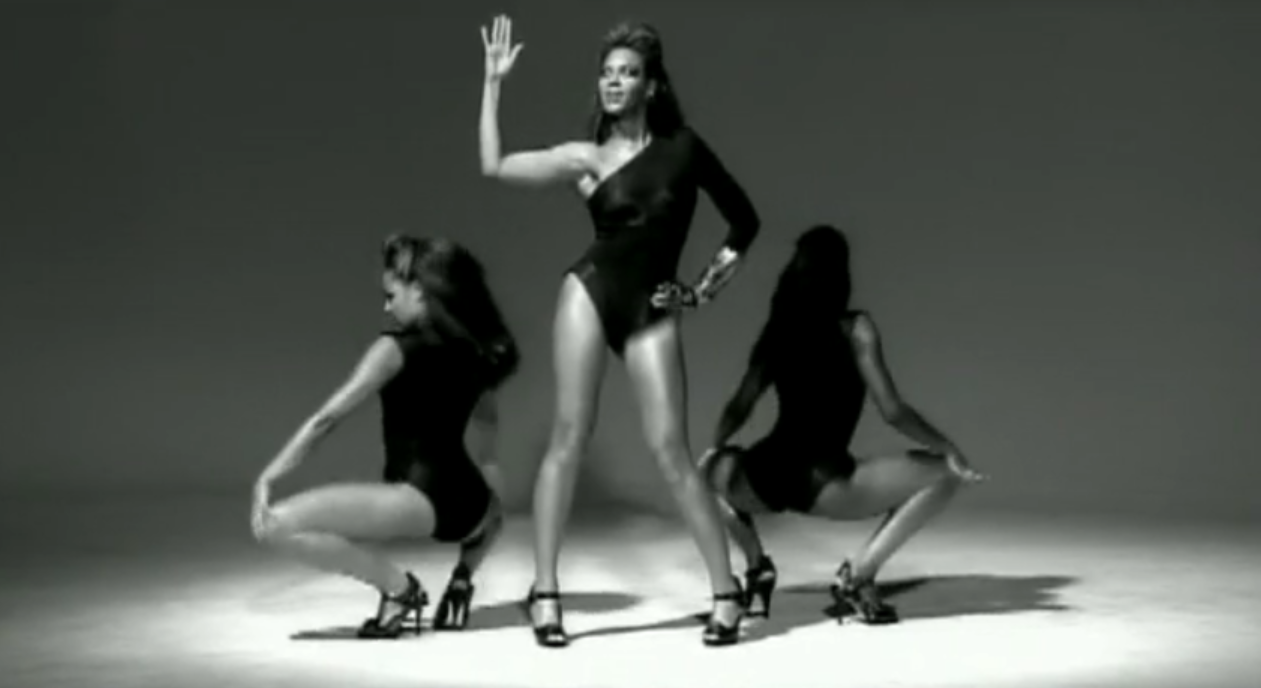

So lately there has been some discussion on the internet about Beyoncé, and whether or not "Single Ladies" is a feminist anthem or a pseudo-feminist anthem or just, you know, a really catchy number with some top-notch choreography and an alluring bionic hand.

A lot of this discussion -- both in the recent AV Club article and in The Sexist -- centers around the word "it" that you are instructed you ought to have put a ring on. From Amanda Hess:

Beyonce uses the dual “its” to objectify herself on two levels: first, as a sex object; second, as a wife. Beyonce asks her man to mark his territory by putting a “ring on it.”

According to the AV Club:

Beyoncé is just a passive “it” that can be claimed with a ring, and that even if the relationship is already bad, that ring has the talismanic power to guarantee a happy ending. Not to mention the idea that a ring will give the unnamed man in the story sole, permanent possession of “it,” since he’s basically just planting his flag in his claimed territory.

That's a lot of interpretive weight to put on a single flimsy pronoun. If we're going to really lay the hammer down grammar-wise -- oh, do let's! -- there are plenty of other things that support the idea that this song has a feminist slant. Beyoncé spends a lot of time telling her ex what he can and cannot do now that they're split: "Now you wanna trip . . . Don't pay him any attention . . . You can't be mad at me." Note that the ex is not allowed to actually trip -- he no longer has the right. He wants to trip; Beyoncé won't let him.

It does get a little weird in the bridge, with this line: "Say I'm the one you own." But there again is the imperative verb, and it is followed by a threat: "If you don't, you'll be alone." The ex's claim to own Beyoncé somehow does nothing to lessen her autonomy in her own mind. There's a little hint of BDSM play here, the verbal equivalent of being handcuffed to a headboard: Beyoncé wants to be a little owned. So play the game her way or she'll ditch your ass.

As for the new fling, he is an accessory like her lip gloss and designer jeans. Twice Beyoncé tells her ex, "Don't pay him any attention." She refuses to let this become a dude-versus-dude match, a competition between the ex and the new guy where Beyoncé is a property that can be earned. She always brings it back to the ex's failings in his relationship with her, before this new guy was ever around: "Cause you had your turn / And now you're gonna learn / What it really feels like to miss me."

One of my favorite moments in the video is when Beyoncé literally brushes off the new guy as unimportant:

The video really does make this all about Beyoncé. She is the entire world -- there is no one else here, no ex, no new guy, no set or props even. There is no dude here to enjoy her sexy dance -- the camera doesn't even care about the backup dancers (who are Beyoncé clones). And yeah, the video is sexy -- because hot damn, Beyoncé can move. Her body is powerful, strong, in constant motion. She displays her control of her body as much as she displays her body itself.

The editing style -- editing being the visual equivalent of grammar -- is part of what makes Beyoncé seem so powerful here. The takes are really long for the choppy ADD world of music videos, and there are plenty of tiny barely visible jump cuts that exist to make the takes seem even longer than they are. Mostly the stays moving, bobbing slightly forward and back and turning occasionally so that the viewer is constantly forced to reorient on the figure of Beyoncé, always near the center of the frame. When the camera does zoom in for close-ups, they focus exclusively on her face.

For contrast, let's look at two other megahits whose videos are polar opposites of "Single Ladies" (assuming things can have more than one polar opposite BEAR WITH ME HERE). The first: Britney Spears' 10-year-old (really? wow) "Oops! . . . I Did It Again" video.

Here are three stills:

This is so male-gazey that it creeps me out. Shut your face, astronaut man!

Viewed after "Single Ladies," it's like watching a train wreck -- quick cuts, shots of Britney lolling on a bed making orgasm-legs, slow-motion shots of just her body in red vinyl, extreme close-ups of various parts of Britney's body, the smiling astronaut and his NASA buddies for whom she's putting on a show. Britney doesn't so much dance as strike a series of poses. And there's at least three of her: dancing Britney (full shots), singing Britney (shot from the boobs up), and lounging Britney (flat on her back and shot from above). You never know where Britney "really" is and you don't know what Britney really wants -- which of course is the upshot of the song, after all.

An even more extreme example is provided by the opening thirty seconds of Kanye West's "Gold Digger": The lingerie-clad woman is reduced to a series of images of her parts: face, boobs, hair, ass, all overlapped at seizure-courting speed. (And then the parade of pin-ups begins.) As for Kanye, he doesn't even turn toward the camera until about halfway through the video. Makes me wanna do this the whole time:

You show him, bubblegum-tongue lady.

You show him, bubblegum-tongue lady.